Why Renewables Can't Get Us to NetZero

The wicked problem at the heart of renewables

Renewables are never going to be able to get us to a clean hundred percent renewable future, and they’re not going to get us to NetZero either. Here’s why:

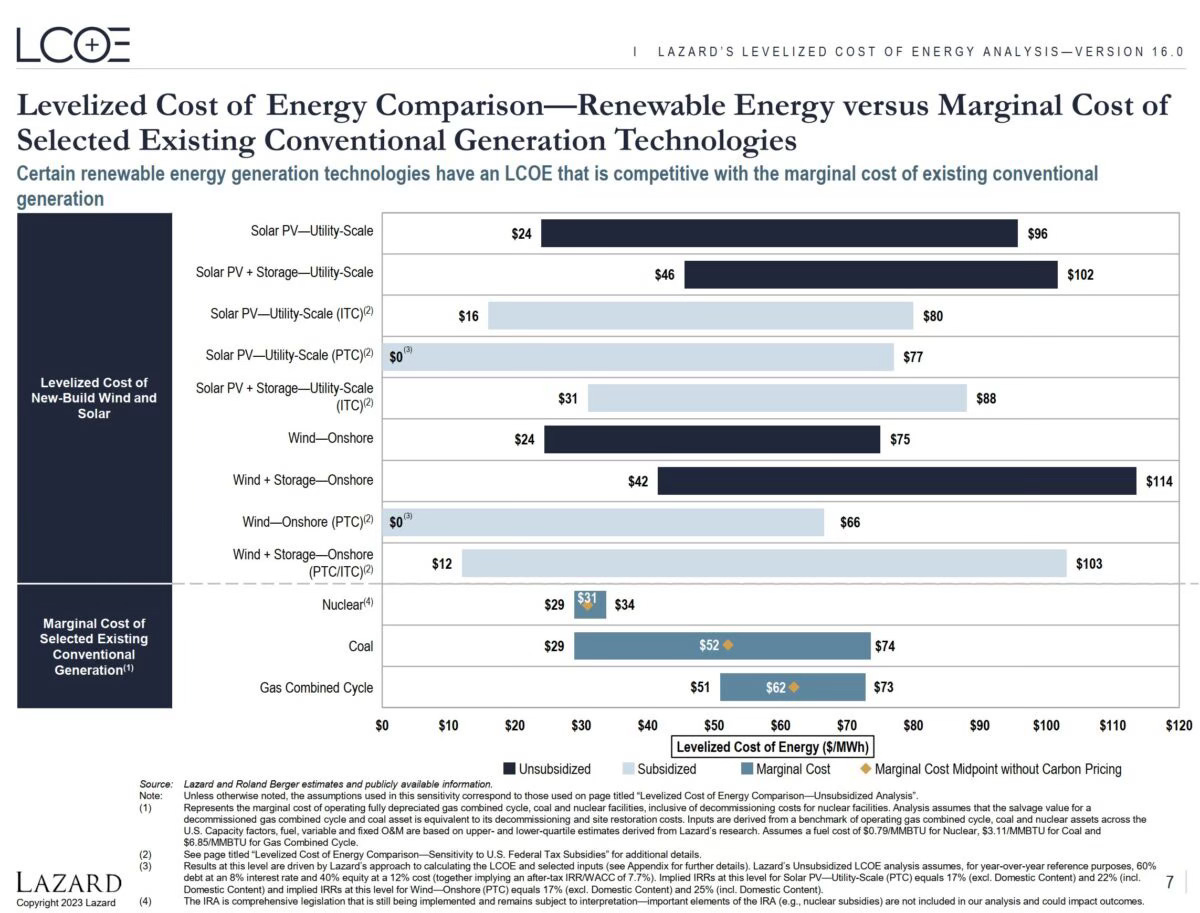

Renewables are intermittent, that means that you need to build more than you need, if you need 5MW supply you (notionally) need 7MW of renewables. Having that spare 2MW of capacity around needs to be incentivised, so you end up paying for the excess capacity to enter the market. As over capacity increases the incentive required gets larger.

You can try to get around this by offsetting your supply, but this means building storage, and lots of it.1 This adds cost, the more we overbuild renewables the more the storage required and the greater the cost. For renewables the arrow of cost points in one direction, up.

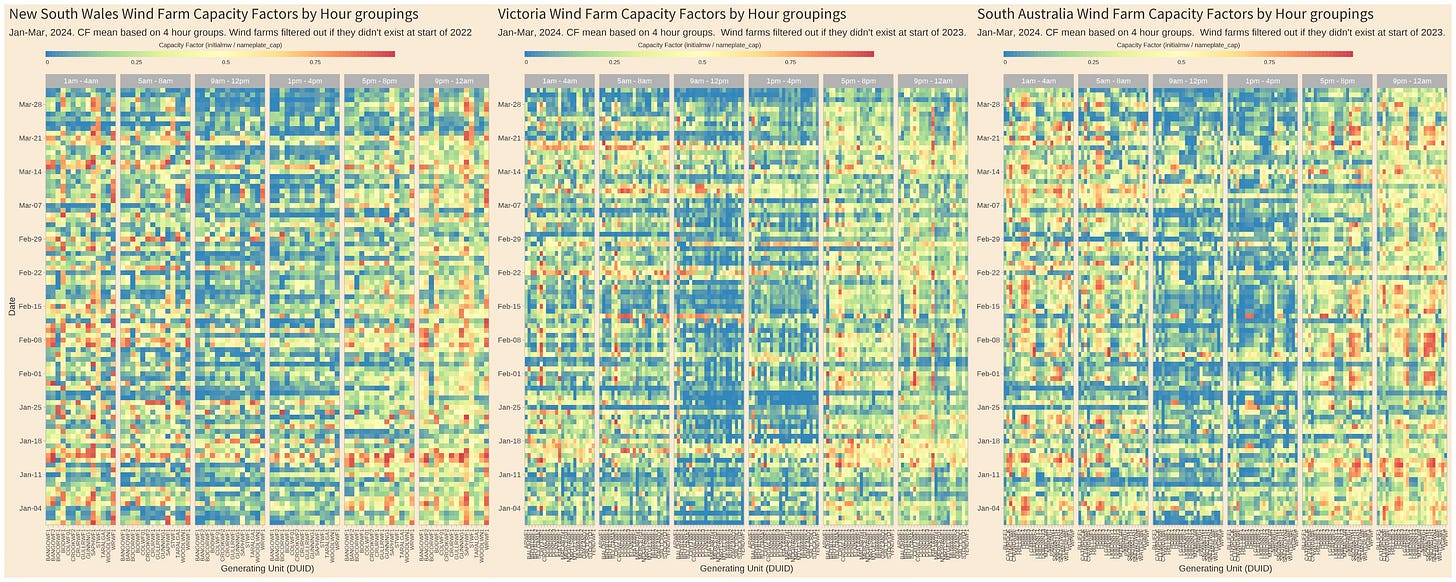

Renewables also (unfortunately) correlate that is it tends to be windy or calm, sunny or cloudy all over at the same time even at continental distances.2 So all that overbuild is regularly generating way too much power and results in the network manager curtailing generation.3 The more you build the worse this gets, having to curtail means you can’t sell, or if you can you have to sell at a negative price, and that makes your renewable generator less economic or causes the generator to engage in complex bidding behaviour trying to avoid it.

What adds insult to the injury of (3) is that low capacity factor (but cheap) renewables (such as rooftop solar) then slays higher capacity factor but more expensive renewables like wind in the merit order effect. Rooftop is particularly bad because it’s subsidised to hell but you can’t turn rooftop off, so every other generator takes a hit accomodating that wild power in the network.4

Renewables (particularly wind) are distributed and also sensitive to siting.5 Generally the next site will always be further away adding more network costs, For wind farms the next site will be also tend to be less windy than the last site. As a result for the same (or greater) build price you get less power, have greater network costs, and have to charge more to recover your costs.6

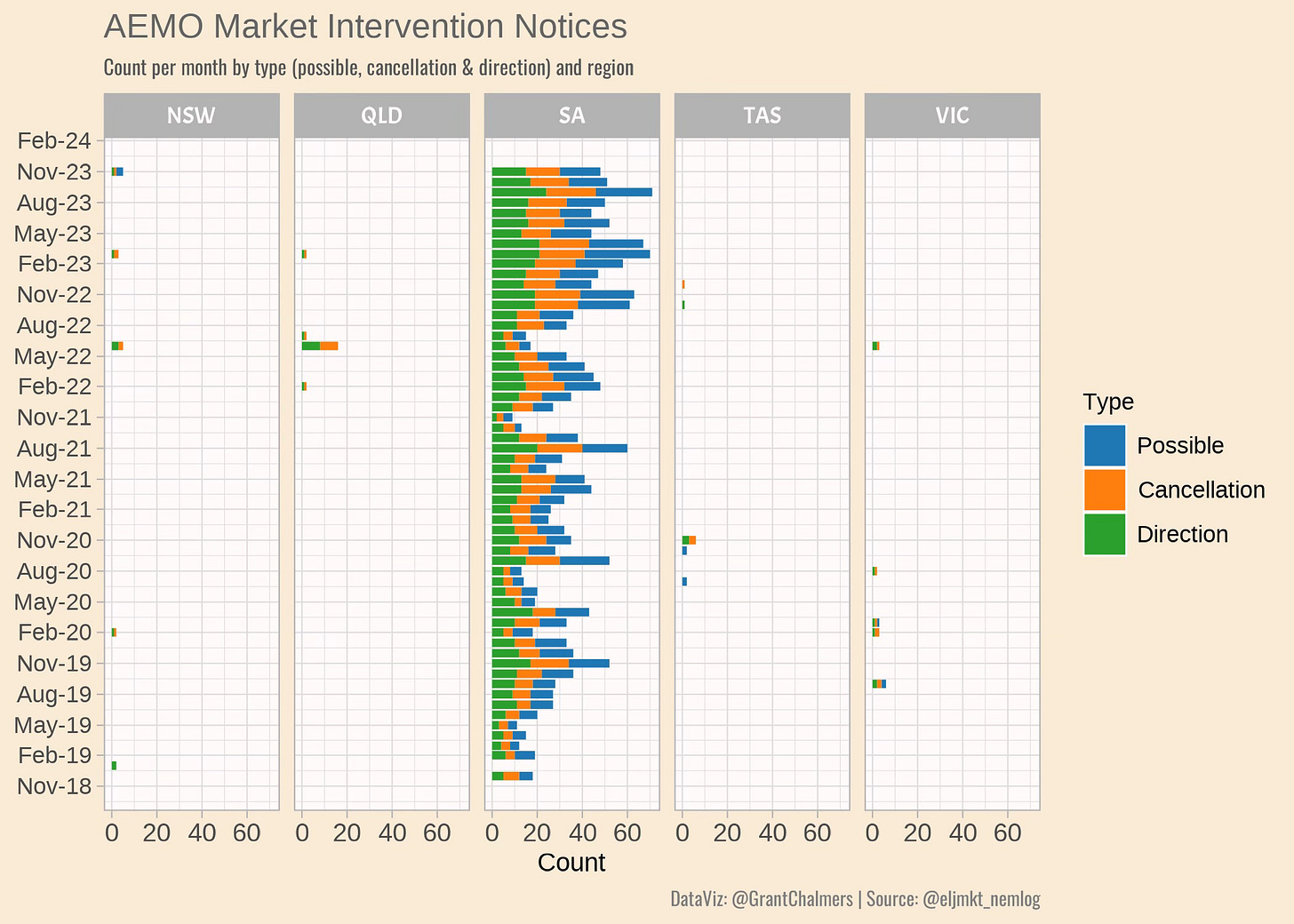

So far we haven’t considered the network other than as a way to transport power from a. to b. So let’s do that now. As you add cheaper renewables you also lose dispatchable (fossil fueled) power generators whose spinning turbines provide grid stability in the form of `inertia’ as well as the ability to ramp up and down to match demand. So more renewables means less stability and ability to compensate for sudden changes in renewables meaning the grid gets less stable and prone to breaking in a catastrophic fashion, as the Spanish blackout in 2025 illustrated. You certainly can add-on inertia to wind-turbines using power electronics, add condensers to the network and play around with faster demand response, but all this adds network cost and complexity to your renewables solution.

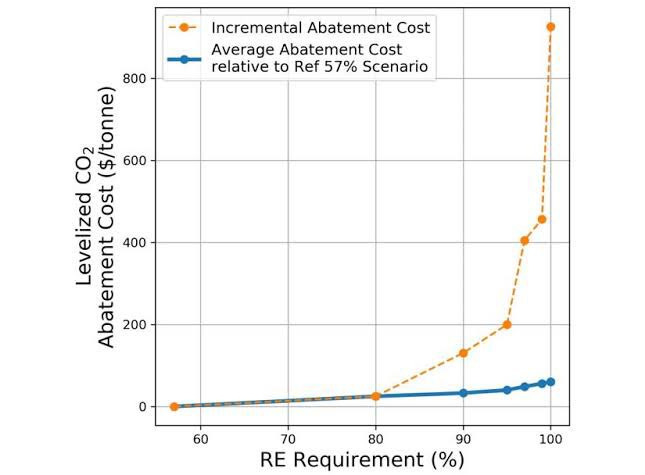

All of which results in the marginal cost of renewables increasing.7 Worse it increasing not in a linear fashion, but as a power law because of all the effects we have described above.

Finally the various renewables storage and generation technologies are now reaching the limits of their respective learning curves. So we can’t rely on ever decreasing cost to offset the increasing marginal cost of renewables.8

Putting all of this together this means that a renewables solution does not scale in an engineering economics sense. Nor will `cheaper X’ renewables/storage save us, unfortunately the dysergy of renewables is baked into the fundamental economics and there’s no way to end run the problem. We will get to X% of supply with renewables and then the program will stall out, well before we reach some nebulous ‘NetZero’ figure.

Here’s a comparison of Australian states (NSW, Victoria and SA) wind farm capacity factors, the ratio of actual performance to plate performance, over the Australian NEM. What we’d really love is strong negative-correlation (A is good when B is bad and B good when A is bad) but what we actually get is correlation across the day (A good when B good and vice versa) or zero correlation (just toss a coin). This means that adding generators that are geographically dispersed won’t help us (Image source: DataViz

).Compare and contrast South Australia’s interventions, with the highest level of renewables in the National Energy Market (NEM), to the rest of the market (Image source: DataViz

).The same is true for grid level solar generators versus wind farms.

Much like dams, the next site for a wind or solar is always going to be worse than the one before it. Indeed when we look at wind farms we find that downwind turbines become progressively less efficient due to wake turbulence. Likewise for offshore wind farms the wake effect for the total wind farms can reduce the effectiveness of adjacent wind farms. As a sidenote the diminishing returns effect is one of the (many) reasons that the pumped storage Snow 2.0 is a complete dog of a project.

The fixed network cost component is one of the reason why you can (and do) have high retail costs but low wholesale costs. See this ACCC 2023 report for a breakdown of retail energy costs.

Marginal cost is the additional cost associated with producing another MW of power on top of what you already have. The graph below, generated from NREL modelling, shows this increase as the incremental abatement cost with the shoulder occurring at around 80%. In reality (see South Australia) the cost increase kicks in much earlier as this Griffith University report modelling illustrates (Image source: NREL).

That is the time to decrease costs by X dollars doubles for every additional X.